There is no shortage of topics to explore when it comes to crime and punishment. A collaborative project by five criminal justice faculty members from three New Jersey Catholic universities decided to take them all on, and then some.

Two criminal justice faculty members from Georgian Court University, two from Saint Peter’s University, and one from Seton Hall University worked to put everything anyone could ever want to know about the history of crime and the criminal justice system into one publication, the Historical Dictionary of American Criminal Justice, published by Rowman & Littlefield.

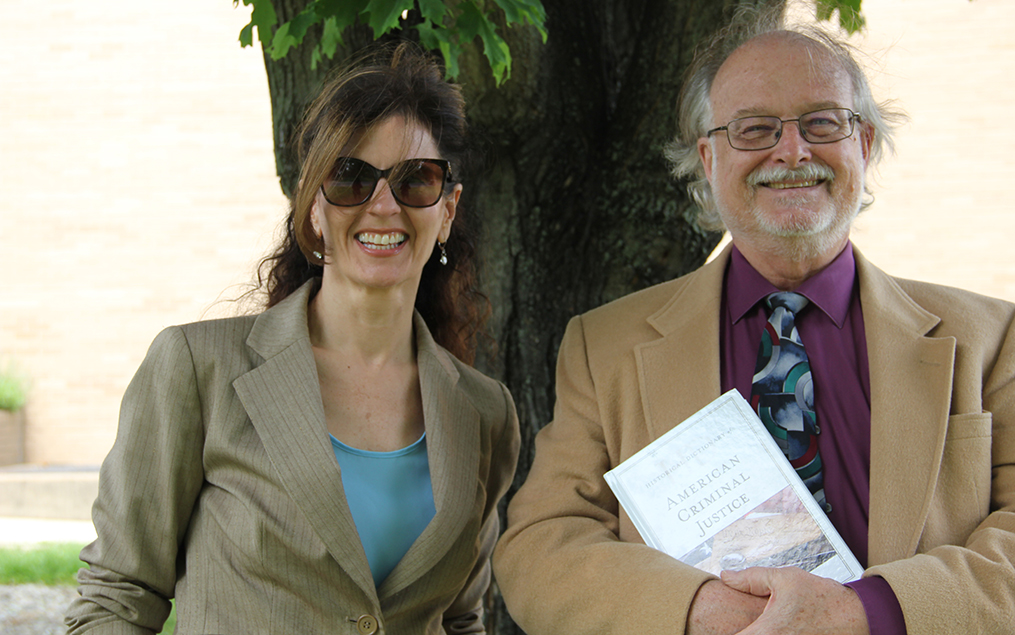

The book not only covers almost 1,000 terms, but also includes a comprehensive introduction, a fascinating account of the development of criminology as a social science, and an expansive bibliography. Georgian Court’s Anna King, Ph.D. and Matthew J. Sheridan, Ed.D., assistant professor of criminal justice and internship coordinator, are two of the co-authors of the 504-page book that examines the historical underpinnings of American criminal justice from A to Z. The book highlights the importance of historical, economic, political, and social contexts that have shaped criminal justice legislation, theory, policy, and practice.

Criminal justice students and academics will certainly benefit from the book, but the authors wrote it with broader audiences also in mind.

“A law enforcement officer would be just as interested in this book as a researcher. It’s got plenty for both,” said Dr. King, associate professor of criminal justice and chair of the Department of Criminal Justice, Anthropology, and Human Rights. “It also appeals to the general public, law enforcement, or other criminal justice academies, and libraries certainly,” said Dr. Sheridan, a part-time assistant professor of criminal justice and the coordinator of criminal justice internships for GCU.

Historical Knowledge and Democracy

As they did research for the book, it became clear how relevant an historical perspective was for today’s world. As they write in the beginning of the book, “There has never been a more important time for those involved in criminal justice policy, operations, and civil service to know their history.

“Emerging across time and place through the fields of philosophy, law, biology, anthropology, and sociology . . . the meanings of [criminal justice terms] are deeply embedded, not only in an historical context, but in complicated social, economic, and political circumstances as well.”

“It definitely struck me how important the history was, especially in the current political climate. It’s important to remember the impetus for current policies and practices,” said Dr. King, who has been an H.F. Guggenheim fellow, a Gates Cambridge Scholar, and a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award fellow.

She is the author of several articles and chapters that examine the relationship between empirical criminology and social reform, the psychology of public opinion on crime, and the role of gender in crime.

“The historical dictionary can provide insights into how a single person’s actions can affect things, “said Dr. King. “As we become more cognizant of our role in a democracy, I think, where would we be without organizations like the Anti-Defamation League or people like August Vollmer, the early 20th-century police chief and UC Berkeley professor who founded the American Society of Criminology?”

Moving Past Prime Time

The proliferation of prime-time dramas often colors the public’s perception of criminal justice. That’s why it’s more important than ever to present facts, definitions, and concrete examples of the system in context, Drs. King and Sheridan said.

“People get caught up in the TV stuff or the movies,” said Dr. Sheridan, “but as professors, we can watch and say, ‘No, no, no. That’s not how it’s done.’ Everybody else doesn’t. They walk away thinking, ‘Wow, is that how the system works?’

One example: a student stood up in his class and said, “Hey, Dr. Sheridan, before we begin, I saw something last night on TV. The warden increased somebody’s sentence. Can they do that?”

The professor’s response to the student?

“That’s why we don’t watch TV. These are the myths that gets perpetrated through bad media.”

The Historical Dictionary of American Criminal Justice is a vehicle for helping readers tread water between reality and myth.

Breaking the Cycle

Another interesting term in the dictionary? Panopticon—a late 18th-century prison design proposed by English social reform enthusiast Jeremy Bentham.

“He’s a bright guy, a British philosopher, and he comes up with an incredibly logical idea for a penitentiary,” said Dr. Sheridan. “It’s got a great name. It’s called Panopticon, and people actually built them.”

But there’s more for readers to know and understand, thanks to the historical dictionary.

“The couple of places [in Europe] that built them regret having built them,” he continued. “When they went to build the first Panopticon here in the United States, it was Eastern State Penitentiary right in Pennsylvania.” The structure, ethics, and philosophy behind it, and its impact on prisoners’ lives have been the topics of debate and study for decades.

Eastern State, which operated from 1829 to 1971, sits in ruins and is better known as a tourist destination than for the reform theories it was supposed to represent.

“People forget their history,” said Dr. Sheridan. “Fast forward 100 years, and we build similar complexes of them in Stateville (Illinois), which then become known as the bloodiest prisons in America.”

“That’s why working on book projects like ours can be so important,” he said. “We are more often in the moment, in the now, as opposed to understanding where things come from or how they got to be the way they are. We fix things without understanding that if we don’t fix the original problem, they’re going to happen again and again.”

Learn more about the Department of Criminal Justice, Anthropology, Sociology, and Human Rights at Georgian Court University, including the online B.A. for degree completers and GCU’s minors in cyber crime, global justice and society, and law enforcement and corrections. The department also offers a master’s degree in criminal justice and human rights.