Oscar Orellana ’15 vividly recalls boarding the school bus for an off-campus outing with his fellow Lakewood High School classmates. They’d signed up to visit colleges and were eager to make the trip.

“I thought I was headed somewhere far, far away,” he says. “But the bus ride took all of 10 minutes and I was like, ‘Hey, why are we stopping?’ I didn’t know Georgian Court University was so close and within reach.”

Today, as an elementary school guidance counselor working in his hometown, Oscar helps youngsters understand that their goals are definitely within reach. The winsome 29-year-old, who also serves as a high school wrestling coach and assists with after-school track and soccer, is Ocean County’s 2016 Guidance Counselor of the Year.

The recognition comes only a year into his first full-time year on the job, and only a year after Oscar completed his M.A. in Education-School Counseling at GCU.

A Champion in His Own Right

Ella G. Clarke Elementary calls itself the “School of Champions,” and inspirational posters, banners, and signs reinforce the message everywhere—in the hallways, in classrooms, and in the main office. The 455 students here are encouraged, supported, and inspired at every turn inside the 70-year-old building.

“Mr. O,” as the students call him, is a champion in his own right. Before he was a standout guidance counselor, Oscar was best known for his wrestling moves at Lakewood High School. The team won lots of matches, he generated publicity for the wrestling program, and it looked as if he might be able to land an athletic scholarship to attend college. Then came his father’s non-cancerous brain tumor. Oscar, the second oldest among five sons, stepped up to help his mother with the family’s catering business and more.

“My mother and I would leave about 5:00 a.m. to get ice for the lunch truck she and my father ran, and get it ready for the day,” Oscar recalls. “Then by 6:30 a.m., I’d help get my brothers ready for school, and get out the door myself. After school, I’d pick them up and walk back to school for wrestling practice, go home, and do it all over again.”

As his father continued to struggle with his health, Oscar’s persistence paid off. He landed a wrestling scholarship from Springfield College and began studying criminal justice. The degree, he thought, would lead him to a steady, respectable job in law enforcement where he could give back to the community.

After a so-so freshman year, Oscar returned to Lakewood during summer break and went to work: he drove a delivery truck, landscaped, and took a job in an appliances warehouse.

He returned to college for his sophomore year determined to do better than the 1.8 GPA he had at the end of his first year. His goals? To make the campus honor roll each semester (check), graduate (check) and to consider teaching. The thought sounded interesting, but it wasn’t until he finished Springfield College, returned home, and actually became a substitute teacher that he realized being in the classroom was more than a job—it was his calling.

Yvette Cucuro, then a district administrator, took notice. There was something about Oscar’s approach in the classroom—first as a substitute and later as a paraprofessional—that set him apart.

“It’s not just that someone spotted him as an athlete and took the time to invest in him. They saw more,” she says, recalling his achievements in high school and college. “I knew Oscar would succeed, especially with exposing our kids to sports. He doesn’t look for the absolute best athletes to participate. He is looking at all students. He works to build their self-confidence, not just a winning record. Oscar understands what we say here at Ella Clarke—that each student has to be his or her own hero.”

“I was assigned as paraprofessional and the idea took root,” says Oscar. “I was so happy. I saw how working with youngsters enabled me to give back. He knew he belonged in the classroom, but with a criminal justice degree, he didn’t have the pre-requisites courses to immediately enter an education graduate program. He applied to GCU, anyway, and studied “like crazy” for his interview with GCU’s Michael Tirpak, Ph.D., who directs the university’s school counseling education program.

He got in and spent the better part of two years attending graduate school, working full-time, and launching a pilot program that paired youth soccer and reading, and included GCU student volunteers. And he did this while helping his mother who, by this time, was battling ovarian cancer.

Leading by Example

Today, Oscar remains just as energetic and determined to ensure his students’ success.

“We tell students there’s always a way to figure it out, whatever ‘it’ is,” says Ms. Cucuro, who is now one of Oscar’s supervisors. “And he takes that to another level. For many of our students, he makes it happen.”

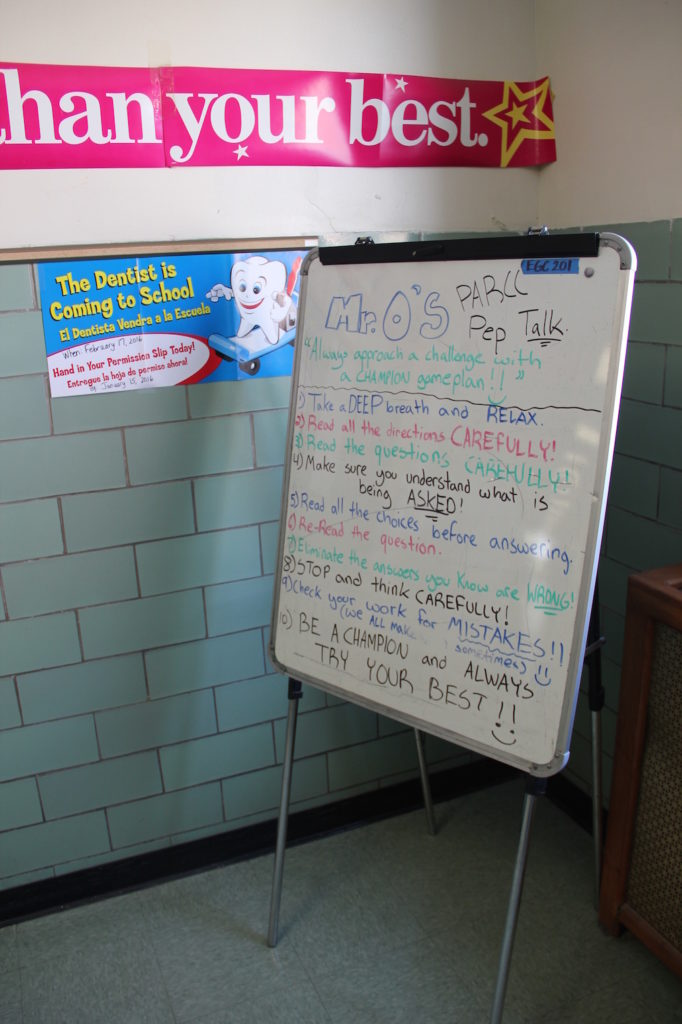

On this particular day, ‘it’ is the often controversial Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC) exam. A dry-erase board outside Oscar’s office offers testing tips.

Relax.

Re-read the question.

Be a CHAMPION and ALWAYS try your best.

“You have to have a plan for how you want to achieve your goals,” says Oscar, reiterating what he tells students. “When you’re a kid, you think you have to be a genius to go to college, but it’s really everyday people who are disciplined, accountable, and committed to finishing what they start.

“When you don’t have family members who have gone to college, no one tells you that.”

Another lesson that he imparts has everything—and nothing—to do with geography.

“I tell them that I came out of Lakewood public schools, and that coming out of Lakewood is not a handicap,” he says. “If you can emerge from a tough environment, it can be an asset.”

And some days are very tough, especially when he has to help students with problems stemming from poverty, homelessness, substance abuse, or family illness. They may not be school issues, but the issues affect school performance.

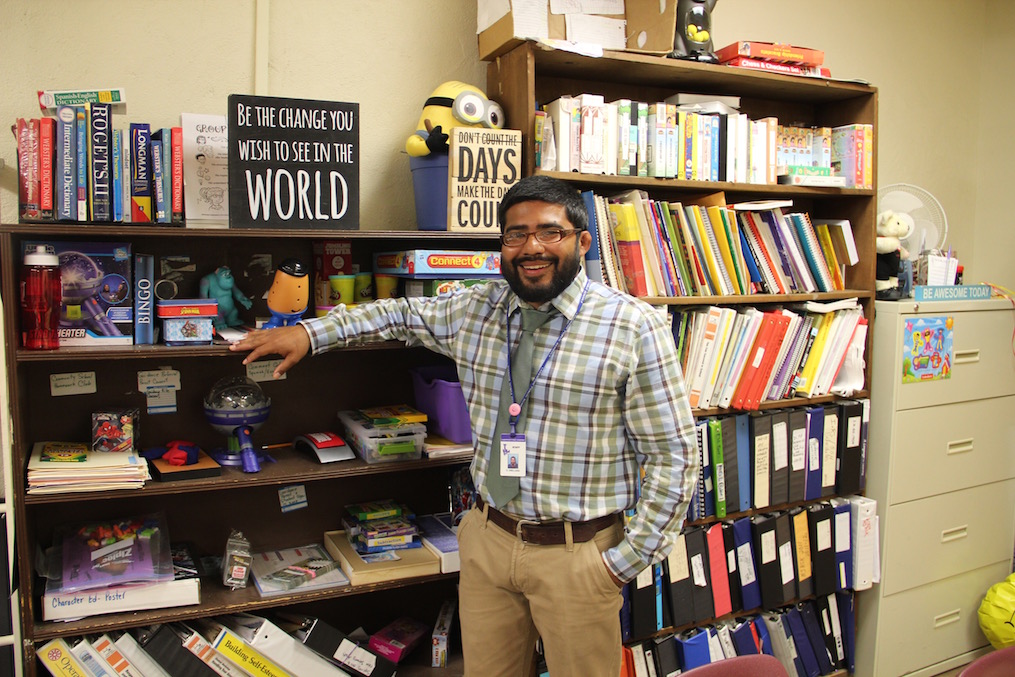

The shelves in Oscar’s office are packed with the tools and tomes that counselors use to address such problems. But amid the research reports, policy manuals, and three-ring binders on character education, anger management, and building self-esteem are lots of games.

Yes, games.

“Mr. Potato Head is one of their favorites,” he explains. “We use him to talk about facial expressions and how your body language can tell a story. Candyland gives an opportunity to talk about chance and how although you can’t always control the next card in the deck, you can manage your choices.

“Jenga is my decision-making game,” he says. “One bad choice can tumble your tower. It’s a reminder to think carefully, strategically.”

What Matters Most

Each day at Ella Clarke brings bright spots and challenges, including finding time to file exhaustive reports, meet with students individually and in groups, get to after-school practices on time, and complete his first-year portfolio, due within a few hours of making time for this interview.

“The biggest challenge I guess comes with knowing all of the great, theoretical things you can do to help children, but having to face reality, which can get in the way,” he says. “There is an enormous amount of paperwork, reporting, and regulatory issues that come with the job.”

And talking about his love of the job while his students complete their last day of PARCC testing makes him especially reflective.

“A human being is more than his or her ability to compute and solve problems,” he says as the clock ticks toward 3:30 p.m., nearly an hour after classes are dismissed. “As an educator you get judged on whether they can divide or read, but it’s fulfilling to know you provide an environment that improves the quality of their lives each day, a place where they can feel safe and learn something.”