It’s nearly 8:30 on a Tuesday night, and after a long day working as pre-professional teachers in local classrooms, six aspiring 20-somethings are now in class themselves.

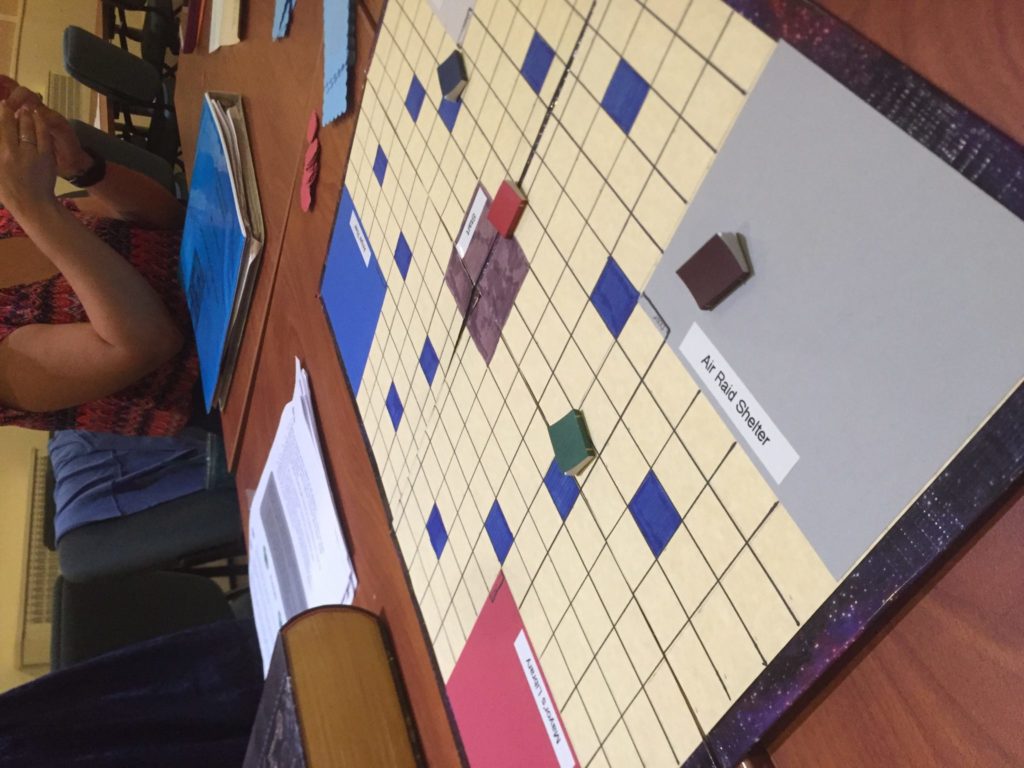

Inside the McAuley Heritage Center, they huddle over a board game, roll the die, and move their multicolored game pieces—tiny books—toward pretend reading rooms. Along the way, they pull cards of chance printed with questions or directives.

“Max must leave, and Papa is sent to work,” one player announces, reading from a blue card that she pulled. “Lose two books.”

A collective groan from the group signals just how engrossed they are at this point—and they’ve been at this for more than an hour, without anyone sneaking a look at their phone, posting pictures to social media, or being distracted by Snapchat or Instagram.

Instead, each player is focused on acquiring the 14 books needed to win the game, created by teacher candidate Erica Dunn and based on characters from the 2005 award-winning title, The Book Thief, by Marcus Zusak.

The board game, meant for four to six players, is meant to be a teaching tool for middle and high school students. And while it is based on a 576-page book, the game moves quickly and goes beyond lessons in literature and reading comprehension.

Erica’s work caught the interest of the European Conference on Game-based Learning (ECGBL) conference, and she presented during their October 5-7 conference at the University of the West of Scotland.

“Erica added another layer to her game by crossing into the content area of history,” explains Nancy Sardone, Ph.D., a GCU associate professor and coordinator for the School of Education’s newest teacher performance assessment system (edTPA). “Although the novel frames the largest genocide, the Holocaust, Erica expanded the game to include awareness about genocides in Cambodia, Rwanda, and Burma,” says Dr. Sardone.

It isn’t easy to explore some of the most disturbing periods in human history—Nazi Germany, Cambodia’s Killing Fields, Rwanda’s 100 Days, or the even the recent annihilation of Myanmar’s Rohingya Muslims. Erica’s board game approach, however, offers students a different way to learn about the past, according to her professor.

“She tied in how society can help prevent future genocides from occurring by raising awareness, making policies, combating denial, and seeking justice,” says Dr. Sardone.

Serious Benefits to Playing Games

Even in a mobile-first, always “on” environment, traditional board games are popular—really, really popular. Industry analysts have tracked tabletop game growth at a steady 15 to 20 percent each year since about 2013. National conventions devoted to board games, crowdfunding campaigns for new games, and the widening use of 3-D printers to make game and puzzle pieces are also fueling the growth.

For educators like Dr. Sardone and those studying to become teachers, playing games can be a a good thing.

“Game-based learning as a broad category has made significant strides over the past 10 years,” says Dr. Sardone. “It is emerging as a powerful instructional tool that positively affects the learning of K-12 students. And because games are goal-oriented,” she says, “they often increase motivation and provide trial-and-error opportunities that help students to develop problem solving and critical thinking skills.”

The power of game-based learning is not limited to history. Education researchers are also evaluating how effective games can be in teaching math, science, language, geography, and computer science.

“By creating immersive experiential learning environments, games draw students in and enhance their ability to process information, make decisions, apply knowledge, solve problems, and collaborate,” says Dr. Sardone.

Games Can Be Engaging, Educational

Erica’s Book Thief board game resonated with her graduate school classmates.

“It really puts the subject matter in a more approachable context, without minimizing it,” her classmate Lindsay Donahue observes as they reach the end of the game—a classmate has “stolen” 14 books, making her the winner and bringing the experience to a close. “You want your students to infer meaning and think, think, think.”

“Students will find it fun, engaging, and competitive,” says Erica, “but we want students to realize that the Holocaust isn’t the only genocide that’s ever happened. It’s something we can’t forget. It’s happening now, too,” she says, referring to the unrest in Burma. “The difference now is that we can stop it.”